And now, the conclusion of my (way, way too long) discussion of running a “cloud” rpg campaign. Confused? You should probably click here.

Why You Should Be Running a Cloud Game (Part 5)

My current “cloud” campaign is a D&D 5th Edition game, set in and around the city of Neverwinter in the Forgotten Realms, and involving just over 20 regular players who rotate in and out each week. We call it “Neverwinter Nights” because that’s a catchy name – not because it has any connection to the video games of the same name.

Rather than bore you with a lot of “inside baseball” or a lengthy description of the various neat things that are happening in the campaign, let’s jump right to some “dos” and “don’ts” that I’ve learned while running the campaign so far. The first is…

In a regular campaign, where the same players will be showing up week after week, it might make sense to go slow, and provide the PCs with a lot of time to casually interact and get to know each other before starting the adventure. Not so in a “cloud” campaign.

Like in a con game, there is no guarantee that any of these PCs will ever meet again. And, like a con game, you the DM have just a few hours to hook the players, deliver the fun, and bring the action to a satisfactory conclusion. That means you must, must, must, at all costs, keep the action barreling along.

So, in our Neverwinter Nights game, every game starts exactly the same: The PCs are drinking at the Bawdy Boar Tavern, have already met, and have already decided to team up and seek out adventure together – at least for tonight. The players wear name tags with their name, race, class, and background to reinforce the idea that they already know each other.

This is not to say that you should discourage the players from roleplaying with each other. By no means! But you cannot let the action get bogged down, especially early in the game.

So, you’ve got the PCs all sitting at the same table, and they’ve bought into the notion that they are going to go on an adventure. What’s missing? The adventure hook!

Please, please, for the love of the gods, do not make your adventure hooks hard to find. In a regular game, if the PCs stumble and fumble around looking for your hooks, that just means you have less preparation work for the next session. But in a “cloud” game, you need to present a (relatively complete) story in a single evening. Losing an hour to “I really thought that old beggar had the adventure hook, as opposed to that lady crying for help for the last half hour” is agonizing and must be avoided.

My sneaky trick for handling this is pretty simple, and easily adaptable to most RPGs. (And, like all my good ideas, it was shamelessly stolen from my friend and excellent DM G-Dawg). In the Bawdy Boar Tavern where all the PCs gather, is something known as “the Shieldwall.”

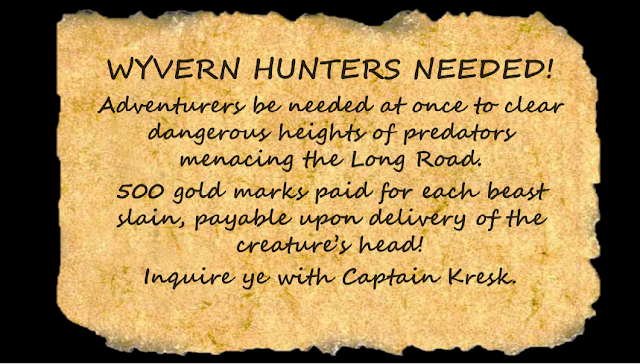

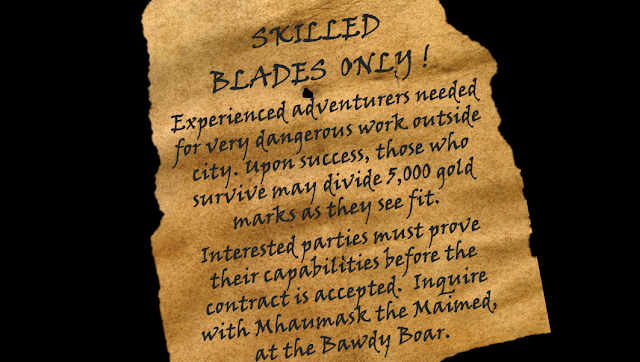

Basically, it is a wall of old shields hung by adventurers who have since retired. As a matter of tradition, anyone seeking to hire sell-swords or other adventurers may post a notice or “want ad” on the Shieldwall.

How does this work in play? Easy. The players know that the various “missions” they can take are posted on the wall. So, as soon as they sit down to game, they can wander over and begin (in character) debating the relative merits of each job opportunity. There is no need to hunt and search for tonight’s adventure: It’s right there, out in the open, in their face, ready to go.

Along the same lines, wherever possible, use handouts, summaries, and lists to quickly convey information the players need. This can be as simple as a hand-written list of the equipment and supplies available to the defenders of a besieged fort. Or, you can get more elaborate…

I’m a big fan of creating Powerpoint slides, like that shown above, identifying all of the NPCs in a particular location who might be worth talking to. At a minimum, I generally do a new slide like this for each session, showing all the potential hirelings, recruits, rivals, and employers present at the tavern when the game starts.

This next one is particularly important. In a normal campaign, the players generally have free reign to wander about and do as they please. That makes it easy to avoid the dreaded “railroading” that drives many players (myself included) completely bat-poop crazy. But in a “cloud” campaign, with very limited time and a different mix of players each session, how do you give players meaningful choices, and avoid boxing them into a scripted plot?

My personal solution is to give them not just one, but several different adventure hooks – each with different challenges, adversaries, and potential rewards. I like to have at least three and as many as five potential “jobs” posted on the Shieldwall – including at least one “easy” job (ideal for brand-new adventurers) and at least one one “hard” job (in case a cadre of stone-cold veterans show up).

So, for example, our last session (game 8 of the campaign) saw a posting about a relatively straightforward job defending a village from Viking raiders…

And a more challenging mission hunting wyverns for the local lord…

And a more dangerous mission for an evil-looking wizard offering lots of gold, but few details…

Not only does this setup avoid railroading, it instantly engages the players, and communicates the message that they are in charge of their own fates. They are free to choose any mission they want. Even brand-new players regularly choose (and often even survive) the most dangerous-sounding missions. And some cowardly (excuse me – “risk conscious”) higher level PCs often go for the easiest-sounding score. Most nights I see a mix of PCs all at different levels, so really any mission can at least theoretically be accomplished. And I’m pretty much always surprised at what mission the players choose.

A Brief Note on “Bounded Accuracy”: In editions past, this sort of setup – where you have PCs of different levels (between 1 and 5) adventuring together – would be difficult to pull off, because monsters that posed a risk to higher-level heroes generally would have been laughably weak and often unable to even hit higher-level heroes. But with D&D 5e’s adherence to “bounded accuracy,” a monster that threatens a 1st level PC can still present a meaningful challenge to even 5th and 6th level heroes. This makes the new edition great for a “cloud” game, in my experience. Want to read more about the concept of “bounded accuracy”? Check out the Old Dungeon Master’s discussion here.

But isn’t this a lot of work? I guess. But remember, each “mission” is relatively short – just 3-4 hours of game play – and meant to be completed in a single session. Also, the missions that are not picked tonight will still be available for other groups to pick in the future, so the work you do is never wasted.

The classic three-act story structure is beginning, middle, and end. True, but not very helpful when planning the equivalent of a series of interconnected one-shot games. Instead, I find it helpful to think of each adventure as comprised of the following three parts:

- The Setting – The particular locale (or locales) where the story will take place.

- The Goal – The specific thing the PCs are out to accomplish. Get the treasure in a wizard’s tomb. Defend a village from attackers. Collect bribes for the corrupt watch officer. Whatever.

- The Complications – The real meat of the adventure, which is not to say it need be overly complicated. This is where you identify the opposition, developments, or surprises that stop the PCs from just rolling in and accomplishing their goal. Once all of the complications are resolved, overcome, or just plain avoided, the session is essentially (over except for tallying up the treasure, of course).

Here’s an example from our most-recent session. The mission the players picked was the “Stand Against the Northmen Raiders!” (above). Here’s how I broke it down for planning purposes:

- The Setting – A small fishing village with a keep.

- The Goal – Stop the village from being destroyed by raiding vikings.

- The Complications – Lots and lots of them. Several groups of vikings are coming in waves. The local lord who hired the PCs is an idiot. Most of his troops have already abandoned him. The rest have low morale and are at risk of deserting. The Lord has personally offended the viking leader, making any truce or bribe very difficult. The lord’s various advisers are more interested in pursuing their own agendas than defending the village. And so on…

Remember, you’re designing an adventure that – from start to finish, hook to denouement – must be completed in a single night. So, you need to boil that adventure down to a very simple concept. But don’t worry – players have a way of turning even the most basic adventure into a raging, five-alarm catastrophe all on their own.

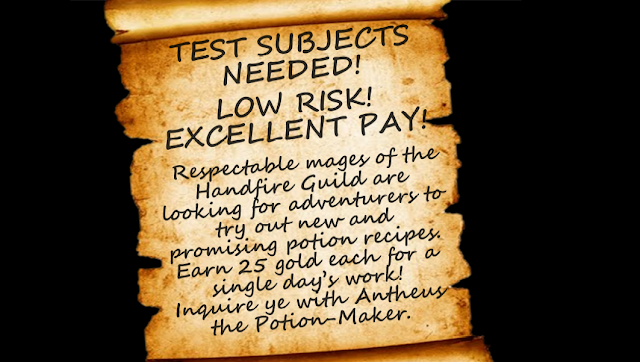

Loot is the best motivator for episodic play. What do a Lawful Good Paladin, a Neutral Wizard, and an evil Monk all want? Gold! But even gold can lose its luster if there is nothing fun to spend it on. A “magic shop” can fix this, but if you are not careful, the PCs will soon be decked out with enough magic swords and trinkets to put even the most jaded MMORPG player to shame.

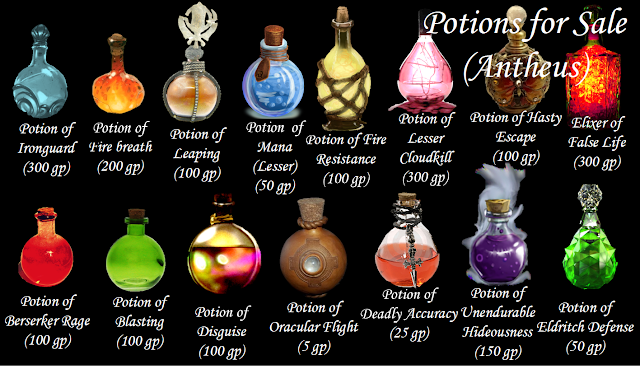

My compromise? The potion-dealer. Potions are one-shot, and their prices can be periodically adjusted to exactly where you need them to be.

Your 1st-level fighter struck it rich last adventure and walked away with a sack of 1,000 gp? Great! Next game he can pour it all back into the local economy by purchasing all sorts of interesting potions that open up new tactical opportunities.

Hopefully this goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway. Steal from everywhere. I’ve plucked maps, encounters, NPCs, and even entire adventures from every source imaginable – ranging from old, TSR-era issues of Dungeon magazine to the One Page Dungeon Contest. Read lots, and steal it all.

The idea is, many different factions are vying for control of Neverwinter. Each mission is either for, or would help, one of the factions. So, when the PCs complete a mission for the Lord of Neverwinter, we color in another piece of the bar graph above the Lord’s crest. If next week’s group completes a mission for the evil Zhentarim, we color in another piece of the bar graph above their symbol. As certain “benchmarks” are reached, certain campaign-world events occur. For example, as the Lord of Neverwinter’s rank increases, he extends his control over more and more of the ruined parts of the city. In this way, by picking the missions that they do (and either succeeding or failing in their efforts), the twenty-odd players are collectively determining the fate of the city they play in.

Above all, remember the best and primary reason to run a “cloud” game – to drink some beer, eat some pretzels, and sling some dice with old friends, casual gamers, and other folks outside your regular, weekly gaming group. So don’t fret about any of this stuff too much – focus on having fun.

~ Balthazar